An epidemiologist testified Tuesday that assumptions in an Allstate claims handling manual about how much force passengers endure in low-speed wrecks have no scientific basis.

“These numbers are impossible, and they are just made up,” said Michael Freeman, an epidemiologist at Oregon Health and Science University testifying in the second day of a $1.425 billion civil trial in Fayette Circuit Court challenging Allstate Insurance Co.’s claims handling practices.

The document estimated the G-force placed on passengers and the speed of a crash based on the type of property damage to certain vehicle models. Freeman said the figures are significantly underestimated and scientifically impossible.

“This is obviously a bogus document,” Freeman said.

Freeman testified as an expert witness for Geneva Hager of Richmond, who claims that Allstate purposefully dragged out her injury claim in a 1997 wreck. Her lawyers argue that Allstate’s claims handling practices, implemented in 1995, violate Kentucky’s Unfair Claims Settlement Practices Act. They are specifically attacking how Allstate assesses minor-impact soft-tissue injury cases, or MIST claims.

Another training manual document estimated G-force for various activities. Freeman said the estimates are absurd, and noted that the document stated that firing a shotgun produces half as much G-force as jumping off two phone books onto a pile of carpet.

Plaintiff attorney J. Dale Golden showed jurors one of the 12,500 McKinsey documents, which were created by an international consulting firm in the 1990s as Allstate redesigned its claims handling. The documents are considered trade secrets by Allstate and have never been released to the public.

For one column, “Trial Defend on Damages (includes MIST),” the opposite column reads, “plaintiff could not have possibly been injured.” Freeman said the document is not supported by science. A large epidemiological study showed that one-third of men and one-half of women were injured in crashes involving $1,000 of damage.

Lawyers for Allstate have denied that it trains its adjustors to assume that minor impact crashes cannot possibly cause injuries. The Illinois-based insurer has said its claims handling processes legitimately apply scrutiny to suspicious and fraudulent claims.

Under cross-examination by Allstate lawyer Floyd Bienstock, Freeman acknowledged that the document about plaintiffs not being injured was not part of Allstate training materials.

Golden began contentious questioning of Allstate executive Christine Sullivan on Tuesday morning. Sullivan denied that the adjuster who handled Hager’s claim was under orders to reduce claims payouts by 13 percent in 1997.

“If that is true, isn’t it a fact that would be inappropriate?’” Golden asked Sullivan.

“Again, sir, I don’t know if I can answer that,” Sullivan said.

“Is that your final answer to the jury?” Golden asked.

Replied Sullivan, “I know that is not how we measure our employees.”

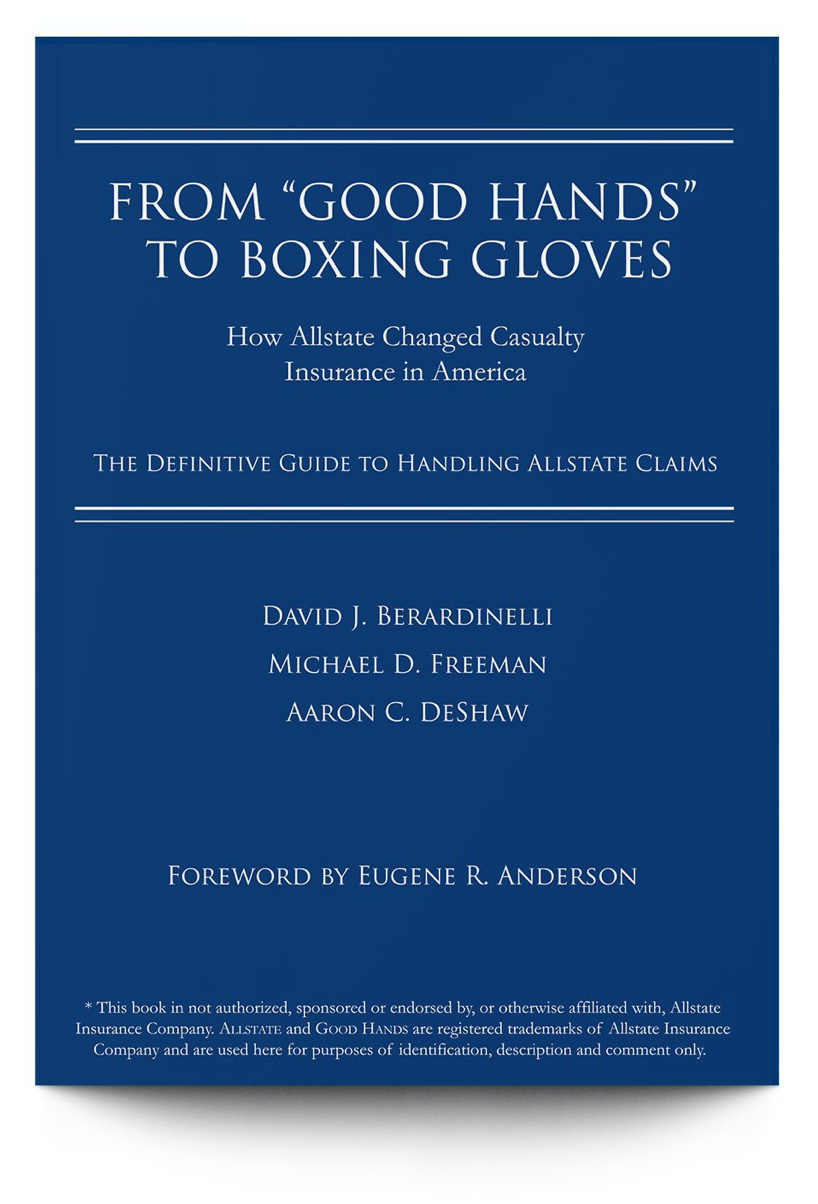

Golden showed jurors a McKinsey slide that plays off Allstate’s slogan. It showed how Allstate wanted to redistribute settlement times. Ninety percent would settle quickly — by accepting paltry offers, Golden says — and get “good hands” while 10 percent of cases would take longer and get “boxing gloves.”

Allstate hired consulting firm McKinsey & Co. in 1992 to redesign claims handling. The new processes were implemented in 1995.

Golden and Sullivan engaged in a lengthy back-and-forth about what the boxing gloves slide meant. Taken in the proper context, Sullivan said, it represents that Allstate wants to make quick, fair offers but is willing to go to trial on cases where it cannot find agreement with plaintiffs who are exaggerating or fabricating injuries.

“It’s a cute way to phrase it, I guess, if you would,” she said. “But you have to look at the whole picture.”

Another document asks, “do we consider bad-faith claims an acceptable cost of doing business.” Bad-faith claims are lawsuits that accuse insurance companies of unfairly handling claims.

In his questioning, Golden said the sentence was really asking whether Allstate considers breaking the law to be an acceptable cost of doing business.

“We don’t violate the law, so the answer to that is no,” she said.

Golden challenged Sullivan on that assertion.

“Haven’t you paid out millions of dollars in bad-faith judgments?” Golden asked. “I’m sorry, more than millions of dollars. Hundreds of millions of dollars?”

After an objection by Allstate, Golden rephrased the question so that it also included payouts in settlements.

“I don’t know,” Sullivan said.